Big History is a method of teaching history about the origins of the Universe and the events that have taken place during its existence. One of the unorthodox aspects of Big History is its lack of emphasis on Human history and how instead it fits that history into the larger context of the universe and history of Earth as a whole (Spier, 2008). Big History pulls from many of the physical and social sciences such as biology, astronomy, geology, climatology, prehistory, archaeology, anthropology, evolutionary biology, chemistry, psychology, hydrology, geography, paleontology, ancient history, physics, economics, cosmology, natural history, and population and environmental studies as well as standard history (Eakin, 2002). Big History’s advantage over conventional history is that it does not provide such a bias towards human history and teaches more about the entirety of Earth’s history. However, there are a number of criticisms of big history such as being “anti-humanist” (spiked-online.com, 2016) as well as not following conventional history standards and instead appearing as more of a telling of evolutionary biology and quantum physics (Sorkin, 2014). There are four main themes other than the sciences listed earlier related to Big History. Time Scales and Questions: A concept of Big History that makes comparisons based on different time scales and notes similarities and differences between the human, geological, and cosmological scales. Cosmic Evolution: A telling of history that focuses on the many changes in composition of radiation, life, and matter in the history of the universe that lead to the creation of humanity and its achievements. Complexity, Energy, Thresholds: A concept in which as the energy increases within materials in the universe increases so does their complexity until they reach a complexity threshold before creating something new in the timeline of Big History. Finally, Goldilock Conditions: These conditions can be described as the conditions required for any complexity to form and continue to exist such as how humanity requires the right temperatures to survive.

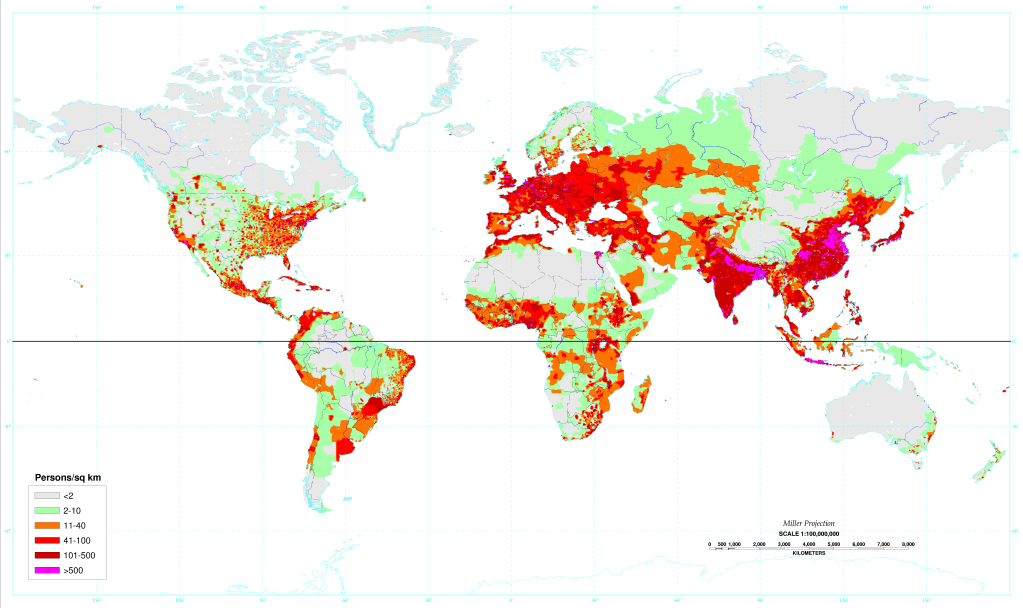

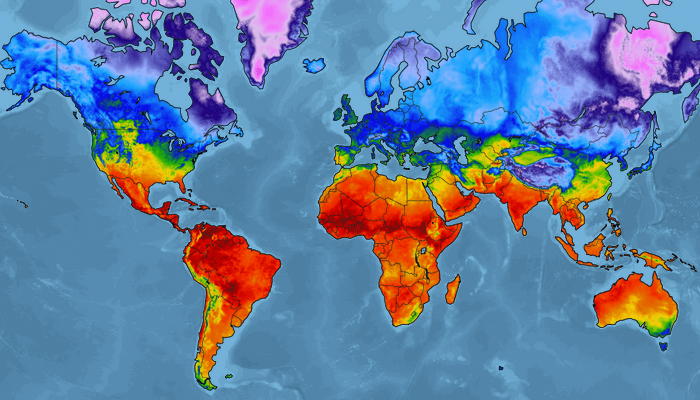

The Map directly above shows a temperature gradient with red areas being the hottest and the pink regions being the coldest. Comparing the two maps above showcases the Goldilock conditions. We can see a clear correlation between the complexity of human society and the proper temperature conditions.

Another and more widely accepted way of analyzing the Earth’s natural history, is through the geological epochs. The Anthropocene is “a proposed geological epoch dating from the commencement of significant human impact on Earth’s geology and ecosystems, including, but not limited to, anthropogenic climate change” (Anthropocene). Another term used to describe this epoch is the Homogenocene which is meant to imply more focus on the diminishing biogeography and biodiversity of ecosystems. This was initially caused through “human predation” and this “was noted as being unique in the history of life on Earth as being a globally distributed ‘superpredator’, with predation of the adults of other apex predators and with widespread impact on food webs worldwide” (Anthropocene). The globalization of human trade took it further because it led indirectly and directly to invasive species spreading around the world. These invasive species play a large role in decreasing global biodiversity. Human activity has also led to the rapid displacement of many animal species into ecosystems and niches they are not well adapted for.

We can also tell environmental history through conventional history. Jared Diamond describes what leads to the collapse of society in his book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. In his book, he defines five factors that lead to the decline of a civilization. However, three of these five factors are environmental issues. These three factors are climate change, environmental problems, and how societies react to the other four factors. Diamond’s book focuses on an environment’s carry capacity as a significant environmental problem that leads to overpopulation and then eventually, the societies’ collapse.

The next segment of the summaries covers U.S environmental history. There are four distinct periods in U.S environmental history, the Tribal era, the Frontier era, the Conservation era, and the current era. The Tribal era was the period that Native Americans lived in North America before the 1600s when European settlers began to arrive. The Frontier era lasted from 1607 to 1890, in which European colonists began founding communities and viewed the natural resources as inexhaustible and nature as something to be conquered and tamed. Early Americans started showing concerns about exhausting U.S resources and went as far as arguing that unspoiled wilderness on public lands should be protected. The government and private citizen sponsored programs began serious focus on conservation programs in the United States during the current era, and these efforts only increased as the era continued. A significant turning point that distinguished the present era from that of the conservation era and frontier era was the Forest Reserve Act of 1891 that put more responsibility on the United States government to protect public lands from resource exploitation. Eventually, during the early twentieth century, two schools of thought came about regarding conservation. The first was the conservationist who believed in preserving the United State’s public lands for science and efficient use and sustainable extraction of resources. The second was the preservationist, who thought it was the government’s responsibility to protect the United State’s public lands in a natural state with no interference.

The rise of U.S environmentalism quickly rose among the united states populace after World War 2. The primary belief of environmentalism was that industrial production and its following patterns of consumption created ecological instability that could bring the viability of modern societies in question.

My first reaction to the Big History concept has to be agreeing with some of its critics. It does seem difficult to distinguish what a physics or biology class would cover and what Big History would cover. However, despite the seemingly deep intertwining between Big History and other fields of science, I do believe there is a place for it when discussing history. Despite not being human history, concepts such as geological dating for epochs show similarities to how we record conventional history. Archeologists use carbon dating to identify what period a human artifact is from using the same procedures they would use to determine which epoch a dinosaur lived. I do not think Big History should outright replace conventional history; conventional history is convenient for focusing on the achievements and actions of humanity. However, I think there should be some intermediate mix between Big History and conventional history that can focus specifically on the growing influence humans had on Earth’s geology and ecosystems during the conventional history periods.

I think that this intermediate mix of the two would look something similar to the U.S environmental history readings we read for this blog post. That reading focused on the political aspects and developments that influenced the environmental philosophies and policies that were present and passed in the United States. However, I believe that it would be better to focus on what actions people took that lead to our harmful influence on the Earth’s ecosystems and geological resources.

How do ancient American societies fit into Diamond’s five factors of collapse? How would cities such as Cahokia, Tikal, and others that do not have any definite signs for a cause of decline be categorized?

Word Count:1158

Bibliography:

Fred Spier (2008). “Big History: The Emergence of an Interdisciplinary Science?”

Emily Eakin (January 12, 2002). “For Big History, The Past Begins at the Beginning”. The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

‘Big History’: the annihilation of human agency”. http://www.spiked-online.com. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

Sorkin, Andrew Ross (2014-09-05). “So Bill Gates Has This Idea for a History Class …” The New York Times.